New York’s Story in Wilderness Conservation

A Civic Conversation with David Gibson

Part I

As managing partner of Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve, David Gibson helps to lead the same organization that Paul Schaefer founded in 1945. As such, he continues to help lead efforts to enforce the Forever Wild provision of the New York State constitution and related laws. Dave has written extensively on the Forever Wild through line that runs from Verplanck Colvin, through John Apperson, through Paul Schaefer and ultimately to Howard Zahniser and the Wilderness Act of 1964, the landmark legislation that created the National Wilderness Preservation System, which today protects more than 110 million acres.

As managing partner of Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve, Dave Gibson helps to lead the same organization that Paul Schaefer founded in 1945. He’s also a part owner of the Beaver House, the cabin Paul built in 1963.

Much of this story takes place in what Paul Schaefer called "cabin country," a "tiny east-central part of the historic Adirondack mountain region" located in western Warren County.

This is where Schaefer and Zahniser both owned cabins on Edwards Hill Road.

David today is one of several owners of the “Beaver House,” the cabin Schaefer built in the 1960s on a 50-acre parcel near both the original homestead that Schaefer’s parents bought in the 1920s and a cabin that Paul and his brother Vincent bought a few years later in 1926.

These cabins sit on the edge of the Siamese Ponds Wilderness which -- at 114,010 acres -- is one of the larger designated Wilderness areas managed by the Department of Environmental Conservation.

“By the 1990s, Paul didn't have a lot of assets other than his home,” David recalls. “He said it would really be helpful if we could get some friends to share in the ownership of the Beaver House and help pay the taxes. I said I'd be glad to join that effort and about five other friends of Paul did as well. There are still a few owners of the Beaver House, and we're very grateful for that because that's our link to that history and to those wonderful people that helped the Schaefers settle there.”

In a Civic Conversation cohosted in February by Skidmore College senior Ellen Turpin, David reflected on his own long career in wilderness conservation and the contribution made by the Schaefer family to New York’s wilderness conservation movement. Following is an edited transcript.

Please tell us a bit about your childhood and any early experiences that led you to decide to devote your career to wilderness conservation.

I'm a New York City boy. My father worked in the textile industry. When he was laid off by the William Skinner and Sons, he became a consultant working in a high-rise building way downtown. Every June when school let out, we would pack up our station wagon and head to Maine. That's really where I got my love of the outdoors, thanks largely to my grandmother and my parents.

My grandmother and grandfather canoed in northern and western Maine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When she was young, she would go up Moosehead Lake, the Penobscot and the Allagash rivers. She had guides, canoes, paddles and pack baskets that were made by Native Americans. She brought those back to a home that was in her family and that's where my family and I went every summer.

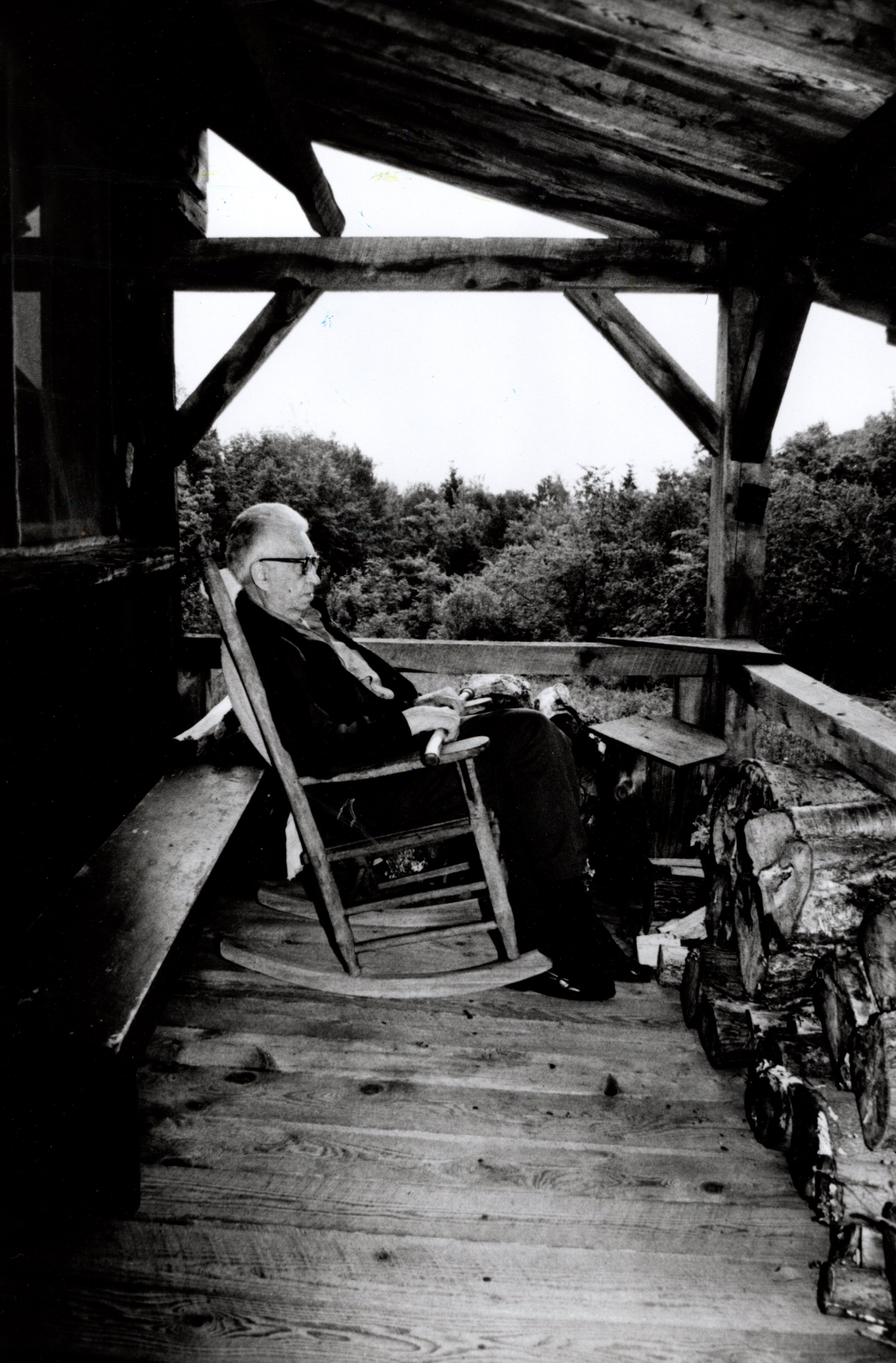

Unable to drive in his later years due to macular degeneration, Paul Schaefer still enjoyed sitting on the porch of the Beaver House.

My parents were able to send me to a summer camp, which broadened my horizons of what Maine was. I spent a number of summers there, and then ended up being a camp counselor. So like a lot of Adirondackers, I started off as a camper, then became a counselor and that really started my love of the outdoors.

I wasn't that competitive, so I wasn't into water skiing or sailing, but canoeing fit my personality very well. I took kids canoeing on the Allagash, or hiking up to Katahdin Mtn, and all over Maine. There you really begin to experience who you are and I really enjoyed those trips.

The Massachusetts Audubon Society was a leader in offering internships and I was lucky enough to get one with a woman who was absolutely amazing. In 1967, she started a K through 12 environmental education program in her school district in Connecticut, called the Mill River Wetland Committee, and was still running it by the time I got there in 1979. I was her first intern with a focus on watersheds, looking at what happens on land ends up in the water.

That's where I met Susan, the woman I love. She lived upstate NY, in the northern Catskills. We went overnighting in Blue Mountain Lake one year, and froze. That was my first introduction to the Adirondacks.

When I arrived in upstate New York, I got an internship with DEC. I ended up meeting two mentors who were outstanding: Charlie Morrison, who was a planner with DEC, and Al Mapes, director of the Five Rivers Environmental Education Center outside of Albany. Those two guys inspired me to to pursue whatever I could and so I got internships through them. Those eventually led to a job with at NYS Office of Parks and Recreation at Saratoga Spa State Park, which I enjoyed.

I ended up helping my friend and colleague Ray Perry in the Parks Office put together a lecture program called "Views of the North Country." That's when another influential mentor, Tom Cobb, manager of Spa State Park, said, "I know Paul Schaefer. Let's get him to deliver a lecture.

Paul came with his Bell & Howell projector and his film, The Adirondack: The Land Nobody Knows. That was my introduction to Paul Schaefer.

Several years went by and I was job hunting again. I signed up for an interview with another nonprofit conservation organization in New York City and took the Amtrak down. On the Amtrak were two older gentlemen and I couldn't help but overhear them; they were just ahead of me. They were talking a blue streak about the Adirondacks and this organization called the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks.

They clearly were going to a board meeting. And I was just glued to their conversation. They were talking about hiring a person and their doubts about whether they could afford it. And one of them was Paul Schaefer, the man I had met at the State Park. He was talking to a fellow trustee named David Newhouse, both of whom are tremendous leaders of conservation and the Adirondacks. I just sat and listened to them. It turns out I didn't get the job with the other nonprofit in NYC and remained with State Parks. The next thing I knew, Tom Cobb, my Spa Park mentor, said "They're hiring at the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks" and gave me a job description.

"I strongly encourage you to apply," he said. So I did, and I got the job. This was late 1986 and I started in the new job in January, 1987. As executive director, I rapidly was made to realize that this was a group that had formed nearly 100 years earlier.

I was their first executive director in 77 years, and a lot was expected of me. Paul Schaefer was vice president, a position he had held since the late 50s. That's where I really met Paul, and it went on from there.

Where does Adirondack Wild fit in the history of wilderness conservation in the Adirondacks?

Even back in the 30s, there were a lot of organizations. Most were voluntary until well after World War II and through the 60s. They began hiring in the 70s. The Adirondack Council had just formed in 1975 and had staffed up. The Adirondack Mountain Club of course had a staff. And gradually I was introduced through Paul Schaefer to the sportsman organizations, including the New York State Conservation Council.

Crane Mountain looms over the hamlet of Bakers Mills, where the Schaefer family began spending summers in 1921.

If not for Paul, I would never have been introduced to them because Paul was a hunter and a fisher, I was not. He had the kind of contacts that no other environmentalist or conservationist I knew had. He believed the hunters and fishers of the Adirondacks were the bedrock of the conservation movement, and without them you would fail in your efforts.

Our organization at that time was very much a white male environment that came right out of its founding in the early 1900s. Most board members were wealthy, white, and male, and all had Adirondack camps of various kinds in various places. We had to change.

Barbara McMartin was among the women we invited to join our board. Wow, what a force -- her energy and ideas. A few other women also joined. I wanted us to be more of a civic, active organization, making sure that the Forever Wild provision of our state constitution had integrity and strength, and that state officials followed it. Accountability was important for all of our state officials -- the Adirondack Park Agency, the DEC, governors, and legislators.

So I was introduced to all of that scene, and was expected to attend APA meetings in Ray Brook. I joined the Forest Preserve Advisory Committee of the DEC.

Paul Schaefer was part of all of this, but he was in his late 70s by then and said, "Now it's your turn. You go and represent me on those committees." So I did that.

Then I realized there's a whole other part of the Association and that was its library and archival aspect. Who holds the archives to this conservation history? Who remembers? Well, Paul remembered back to the 1920s and Dave Newhouse remembered. He came on the scene in 1945. We were expected to be the repository for a lot of that archival history and the Adirondack Research Library came into being before I came on the scene, in 1979-80. It's a really important component of what we took on, maintaining and moving a library about the Adirondacks for the public to use.

You're a part owner of the "Beaver House" that Paul Schaefer writes about in Adirondack Cabin Country, but this wasn't the first home he knew on Edwards Hill Road. Can you tell us the history on this?

The Schaefer family settled in the summer in 1921 because their mother, Rose Schaefer, had a severe form of asthma. Her doctors said she needed to leave Schenectady and take the cure of the Adirondacks -- clean air, mountain air, and balsam. A member of the family found a place.

The locals adopted the Schaefers. In those first summers, they welcomed them, bringing them eggs and milk and enabling them to just soak it all in. It was a very welcoming group of people on Edward's Hill. They were hardworking farmers, hunters, fishers. Some of them had jobs.

The Schaefers didn't have a lot of money, but they did have the things that sustained them through those first summers. That's where the Schaefers settled. Then they bought the house that's still there from a local family. For the first 30 years, Paul had a cabin that Johnny Morehouse owned. Johnny was a mountaineer, as they all would say on the hill there. It was a log cabin that probably dated to the 19th century. So that was the cabin that Paul and Vincent bought in 1926 and stayed until the early 60s. That's when Paul decided to build his own cabin and called it the Beaver House.

He brought in some of the beams from an old building on Sanders Avenue in Albany. When they sanded those beams down to bring them to Bakers Mills, Paul detected what he thought was the odor of beavers, and so he speculated that this probably was where they rendered beaver for the fur industry in the 17th century. It was an old Dutch building, so that's very possible.

The cabin sits within about 50 acres of surrounding woods. It's zoned Rural Use under the Adirondack Park Agency's land use classification, and adjoins the Wilderness area.

A lot of my conversations with Paul took place here or at his home in Niskayuna on St. David's Lane that he built for his family in 1934. Paul had cold hands, and he would build a roaring fire at all times of year, including in June or July, and you'd sit there and sweat and talk to Paul.

We know a lot about Paul as an advocate for wilderness. How about as a builder? What were the signature features of the many homes he built in the Adirondacks?

Big beams. Granville slate roof. Wood lintel over the front door, mantle over the fireplace. Oak floors. A simple but beautiful banister on the stairwell. I don't know how many carpenters Paul hired and fired because they didn't construct stairs well.

Among signature features in homes built by Paul Schaefer were oak floors and big beams. When building a home on St. David’s Lane in Niskayuna for his family in 1934, he sourced some of the beams from Dutch barns. Paul’s former home now houses the Adirondack Research Library, the development of which was a top priority for Dave Gibson.

He had high standards and expected his men to have them, too. Paul was just very handy when it came to structures and he knew how to site and assemble a house. He had learned the carpenter trade in the 1920s. Because he wasn't licensed, he asked C.T. Male to review and stamp his projects. He built many beautiful homes that are still being sold today. He admired the Dutch style so he built in that style. The simplicity and strength of this type of construction just fascinated the three brothers.

There are very few people who could take down a Dutch barn, but Vince did. He could take down a Dutch barn and reassemble it. Some of the beams at the Kelly Adirondack Center came from old Dutch barns.

All three brothers were about three or four years apart. They collaborated on Vince's house in Rotterdam, which is now owned by his son, Jim. Paul very much was involved in that project as was Carl, the "kid brother."

Carl was an extraordinarily skilled mason and could also build. He would insist on never using a motor vehicle. He would use no motorboats to carry the stone for fireplaces, but instead would row that stone out across a lake to the building site. All three brothers were pretty strong and Carl had no fear of heights. Carl would be out there maintaining those chimneys years later.

Linda Champagne, another fine historian from the area, has written articles about Paul's building career that deserve more attention.

There are many people who ask: Do you have a full set of Paul's blueprints? No, they've been scattered to the four winds unfortunately. There are some at the Kelly Adirondack Center, but I don't think anyone has a complete set.

Next week: David talks about Paul's relationships with key figures in New York's wilderness conservation movement, as well as those with brothers Vincent and Carl. And we ask: Why aren't their stories more widely known?