New York’s Story in Wilderness Conservation

A Civic Conversation with David Gibson

Part II

In the first half of our conversation with David Gibson, we learned what made him decide to go into wilderness conservation, how he met Paul Schaefer and ultimately became head of the organization Paul founded in 1946 to fight the Black River Wars.

We learned about Paul as a builder and we heard the story of the Beaver House. Now we explore Paul's relationships with key figures in New York's wilderness conservation movement, including his brothers Vincent and Carl.

We also ask David why New York’s story in wilderness conservation isn’t better known.

Tell us about Paul's relationship with Verplanck Colvin, the pioneer whose work led to the creation of New York's Forest Preserve and the Adirondack Park.

Verplanck Colvin

Paul was influenced by Colvin at an early age. He was just really enamored of his writing. Paul also had a knack for writing, and he had a knack for imagery and poetry in his soul. Colvin, I think, sparked Paul's desire for adventure. Colvin was an explorer, very much like some of the great American western explorers like John Wesley Powell. Colvin had that spirit, drive, and ego, and also the sheer talent and willingness to put up with tough times and conditions.

The Adirondacks just seeped into Paul's blood over time, starting with his arrival with his family in 1921. He started his Colvin collection early in his life and that may have sparked his own writing, which he started as a teenager. He worked on some of the chapters in his three books for years. It took him until his 70s to actually publish his first book, Defending the Wilderness, in 1989.

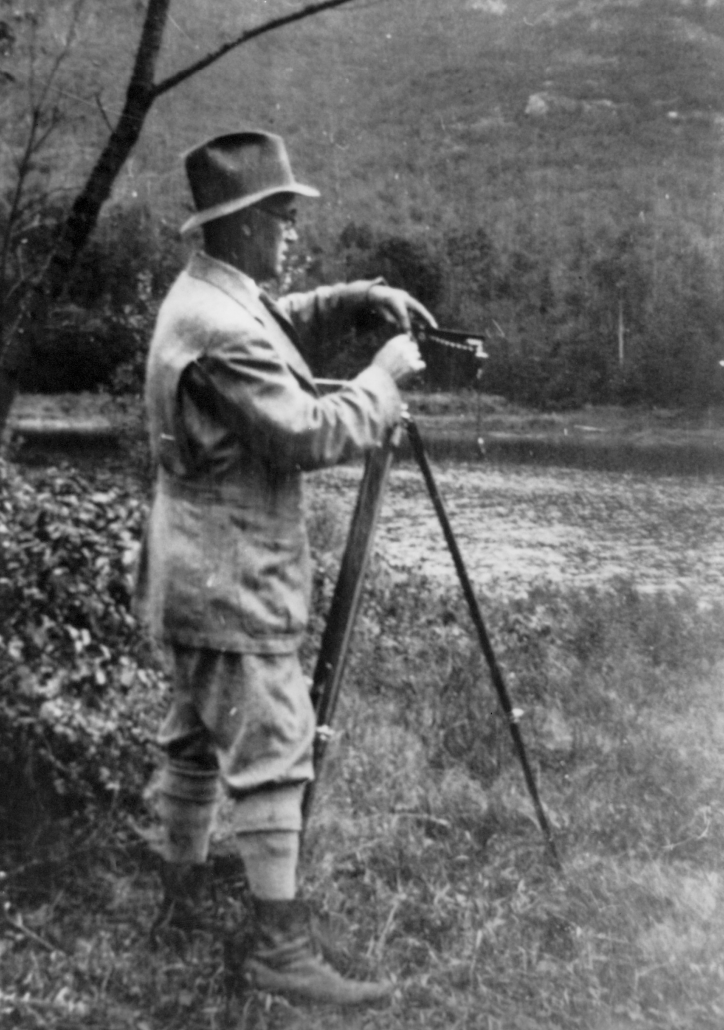

Colvin also took photographs. He did his sketches, which are incredible, but he also took a camera with him. Slow, laborious, heavy -- but he took these beautiful shots. That impressed Paul. He really took it to heart. He used photography and filmmaking to show the public that this was a statewide cause and then a national cause. You had to show it visually.

Tell us about Paul's relationship with John Apperson.

I didn't know Appy, but letters that Paul wrote to him in the early 1930s show he wanted to be an acolyte and that Appy was the leader. He wanted to create a kind of a youth front for Apperson. The Schaefers had helped form the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club, but Paul wanted to do more than early Nordic skiing, skate-sailing or climbing Marcy. He wanted to be active and actually do something on the conservation front. In the early 30s, Apperson was trying to influence a number of issues in the Adirondacks.

John Apperson

They met in 1931 at Apperson's home in Schenectady. Paul said, "We're here. We want to do anything you ask us to do." Apperson had pamphlets he wanted to circulate focused on pressing matters in the Forest Preserve on Lake George and throughout the Adirondacks. Paul said, "I'll deliver them. I'll do it." So, in his spare time, he delivered a lot of pamphlets. Pamphleting was a big deal early in the 20th century. How do you get out 10,000 pamphlets? Well, you just go door-to-door, and Schaefer did his share of that.

Then they would meet again and strategize. Apperson would send Paul out on photography trips. On one, in July 1932 he sent Schaefer up to Mount Marcy with a big camera. Finch, Pruyn Paper Company at the time owned a lot of the land below Mount Marcy down towards Mount Adams and Tahawus. There was a lot of slash on the forest floor that caught fire. It was a hot day. There was a lot of smoke, and Apperson wanted Paul to capture that on film as a conservation statement, showing the need to protect more Forest Preserve. The so-called "Closed Cabin Amendment" was on the ballot that fall. Apperson wanted to defeat it because it would have opened the Forest Preserve to all sorts of commercial uses, allowing cabins, roads and industry.

There was nothing light about going up to Mount Marcy in 1932. Your clothing was heavy. Your equipment was heavy. So there Paul was on top of Mount Marcy and who did he meet by chance at the summit? Bob Marshall. Bob had yet to found the Wilderness Society, but in three years he would. The Marshall family was at the heart of the national and Adirondack wilderness movements.

That 1932 campaign was successful. Voters turned down the Closed Cabin Amendment overwhelmingly and thereby preserved the strength of Forever Wild. And along the way Paul met Bob Marshall, and that was a powerful alliance.

Tell us about Paul's friendship with Howard Zahniser.

Howard Zahniser

Howard Zahniser had gotten the job of Executive Secretary with the Wilderness Society that Bob Marshall had formed in 1935, four years before Marshall's death as a young man in 1939. How would the Wilderness Society carry on without him? The organization had a number of inspiring leaders at the board level, but no staff. And, with the depression, this was a tough time to fund the hiring of staff. But they managed, thanks to a trust fund the Marshall family had passed along. Zahniser was hired in 1945.

In that first year, this national organization met in New York City. George Marshall, Bob's brother, asked Paul Schaefer, "Do you know about this Moose River Plains and the dams that the state wants to build there?"

Paul said, "I know nothing about it, but I had better know something about it." And within a year, he and Zahniser, who was at that meeting, agreed to meet up, and they did.

These were going to be mega dams on the south branch of the Moose River. That alliance gave Paul's campaign a national scope to defeat them. They established a friendship in that first year. Also within a year, Zahniser bought this cabin for $100 down. Paul put down the money for the camp that's still in the family.

They took a trip together into the High Peaks in 1946 that both Paul and Ed Zahniser, Howard's son, recount in their respective books. Several generations of Schaefers and Zahnisers have grown up together on Edwards Hill Road, all joined by this love of wilderness.

To what extent did the brothers Vincent and Carl get involved in the wilderness conservation effort?

They had a mutual admiration society going there. Vince was a scientist and Paul greatly respected the scientists of his day, and there he had one in his own brother.

Vincent became the director of the Atmospheric Science Center in Albany. Vince participated in Paul's films. For example, Vince is featured in "The Adirondacks: The Land Nobody Knows." Vince explored the Adirondacks in his own way and fashion. They collaborated and shared information all the time.

You're the head of the organization that Paul used to be vice president of. How would you compare the issues that you're confronting now versus those that Paul faced?

I think it's an era where we need to be far more inclusive of other people that have not traditionally been part of the conservation/environmental movement. That's a big change and an important change. Conservation/ environment has been a closed shop for many people.

"The experts handle that." "I'm not part of that scene at all." "I'm not white and I'm not male."

For a long time, this was strictly the domain of white males. That has changed. You see many more women leading environmental organizations, and that's really positive. A lot more persons of color are involved, and that's really great, too, The Adirondacks have not exactly been friendly to persons of color. The communities are not that welcoming, but that is changing. That's something the Adirondack Diversity Initiative has really taken on in a very bold and courageous way. That's a coalition effort.

Adirondack Wild is still focused on the Forever Wild philosophy and its main principle is that we don't amend the Constitution unless there's a real public purpose in doing so. There's a public purpose in preserving the Forest Preserve and and all that flows from it.

The Adirondack Park Agency has compromised a lot in its 50 years of existence, and we want to hold the agencies that are responsible for the Adirondacks and the Forest Preserve accountable for their actions. We still think that's a very high priority, as is stewardship. Land acquisition has just come so far since Paul's day. He died in 1996, and there's been a tremendous growth since then in the Forest Preserve and in conservation easements that protect private lands. He would be happy about that.

The next question is: How are you going to be a long-term steward of those lands and not love them to death? This was Zahniser's appeal. He said, "I've created the the National Wilderness Act, but it's going to be loved to death without grassroots people with caring for the lands over the long term. Protection is just the first step."

We're in that period where protection largely has happened -- not in all cases, but mostly. Now we're in a long-term stewardship phase, and that requires resources. The challenge is to acquire the state and private resources to be a good steward of what we have protected.

Why isn't New York's story in wilderness conservation better known?

I wrestle with the question all the time. A lot of the the national wilderness organizations were founded for the western wilderness areas. Eastern wilderness is a relative latecomer -- congressionally in 1978, compared to 1964 nationally. In 1978, Congress recognized that wilderness was not just a western classification, and just because the eastern part of the country had been populated for centuries, parts of it could also qualify as federal wilderness. And so, we have federal wilderness areas in New Hampshire and Vermont, for example, as a result of the 1978 extension of the Wilderness Act. But not in New York, where we have state-owned wilderness.

"The Adirondacks take care of themselves." That was always the attitude. "That's a New York State issue." It took people like Paul Schaefer and others to say in response, "No, the Adirondack experience has national consequences and implications."

There are very few governors that understood that. Franklin Roosevelt understood it. Al Smith knew it. They got involved and, in fact, the Forest Preserve probably influenced FDR when he became president, in the creation of the Soil Conservation Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps. The growth of the national parks probably had their impetus because FDR was governor of New York State and grew up in New York State. He was a birder like his cousin, Teddy, and he knew the Adirondacks. There were battles in the Adirondacks while he was governor, and they influenced him.

The world is a lot bigger and there's just a lot more competition for time, energy and resources. The Adirondack Park has had its moment in the sunshine nationally, and now that the climate battle is really heating up, I think it needs to be once again front and center. A light needs to be shone on the Adirondack Park and the Catskill Forest Preserve as models for the world.

If Paul were able to come back 30-plus years later going and look around, what would be his view of the state of conservation and preservation now?

I think he would be delighted that some of his goals as an elder in the movement. He wanted to see the Finch, Pruyn lands -- 161,000 acres -- protected in some way. It couldn't be done in his lifetime, but he pushed for it. He knew the president of Finch, Pruyn, and they had arguments about what made a more beautiful forest: a silviculture environment where you sustainably cut down trees or more of a wilderness ethic?

He'd be glad that this huge Finch, Pruyn tract has been protected through easements and state Forest Preserve acquisitions.

I think he'd be a little concerned about the coalitions. He would see a weakness there that we're not effectively bringing people together from different walks of life. It's a bigger world, there are more people in it, and there more people who should be included in these efforts. It's a more dynamic environment, and it's not as easy to see us working together as in Paul's day, when he formed coalitions.

Those weren't easy, either. I'm awe of the coalitions he formed. The unions that he brought in. The garden clubs he brought in. He still stands as one of the great, most skillful leaders of coalitions, which made things happen because people weren't all deer hunters. They were not all wilderness fans, but they believed and had common interests in the outdoors.

If we can assemble similar coalitions today, the climate battle is the most important battle we can fight. The Adirondacks are the lungs of New York State, along with the Catskills, Tug Hill Plateau, and so many private forests in western New York. We're the owners of the lungs of the planet here in New York State. Sixty-one percent forested. It's not all wilderness, but the Forest Preserve is a tremendous carbon bank. If you cut down the Forest Preserve, a thousand years of carbon would be released into the atmosphere.

If we don't honor our Forever Wild legacy here, we're in big trouble. As educators, broadly speaking, the Forest Preserve has a lot to say to the world today.